Introduction

While weatherization is one of the most frequently discussed home energy improvement strategies, it is often misunderstood. One reason for the misunderstanding is the variation in how people define weatherization activities. Lost-cost improvements like adding weatherstripping to doors and windows are commonly recognized as weatherization strategies, but cost-effective efficiency measures that address the building envelope, cooling and heating systems, home appliances and even electronic devices can also be classified as “weatherization” improvements. The term “whole-house weatherization” extends the traditional definition of weatherization to include installation of modern programmable thermostats, energy-saving cooling and heating equipment, or repair of old, inefficient equipment (water heaters, air conditioners, and so on).

A house is a complex and interconnected system of materials and technologies (i.e., the house) and human behaviors (i.e., the people). The purpose of this system is to provide a comfortable, safe, healthy, and sustainable indoor environment in which humans can dwell and find shelter from the ever-changing elements, seasons, and natural events of the Florida environment. The “whole-house” approach to weatherization addresses how a home performs as a system, identifying opportunities to improve the efficiency of the building from its envelope to its technologies to its occupants’ behaviors.

The benefits of weatherization begin with reducing the energy bills of recipients for a long period of time. Some measures, such as insulating walls or roofs, for example, can provide savings for the lifetime of a house—30 years or more. Other measures, such as making heating or cooling equipment more efficient, will provide savings for 10–15 years. On average, the value of the weatherization improvements is 2.2 times greater than the cost.[1]

The Many Practices of Weatherization

Typical weatherization activities aim to benefit the health and safety of the home’s occupants while reducing energy use and utility bills. The process of weatherization, however, is never complete and requires ongoing attention to maintaining the building envelope as it continuously degrades under the changing balance of interior and exterior forces.

Basic Weatherization Practices

The most basic, lowest cost, and well known practice for home weatherization is simple sealing of air leaks along doors, windows, and penetrations through walls with caulking and weatherstripping. While the following air sealing practices might be included in basic weatherization practices, without the benefit of conducting a blower door test, we can only assume that air sealing efforts address unwanted air infiltration. It may also be beneficial to seek the feedback from the local utility or energy rater in prioritizing weatherization activities.

Basic weatherization practices might include:

- Properly insulating your hot water plumbing pipes.

- Sealing bypasses (cracks, gaps, holes), especially around doors, windows, pipes, and wiring that penetrate the ceiling and floor, and other areas with high potential for heat gain/loss. These bypasses can be sealed with caulk, foam sealant, weather-stripping, window film, door sweeps, electrical receptacle gaskets, and other similar materials to reduce infiltration.

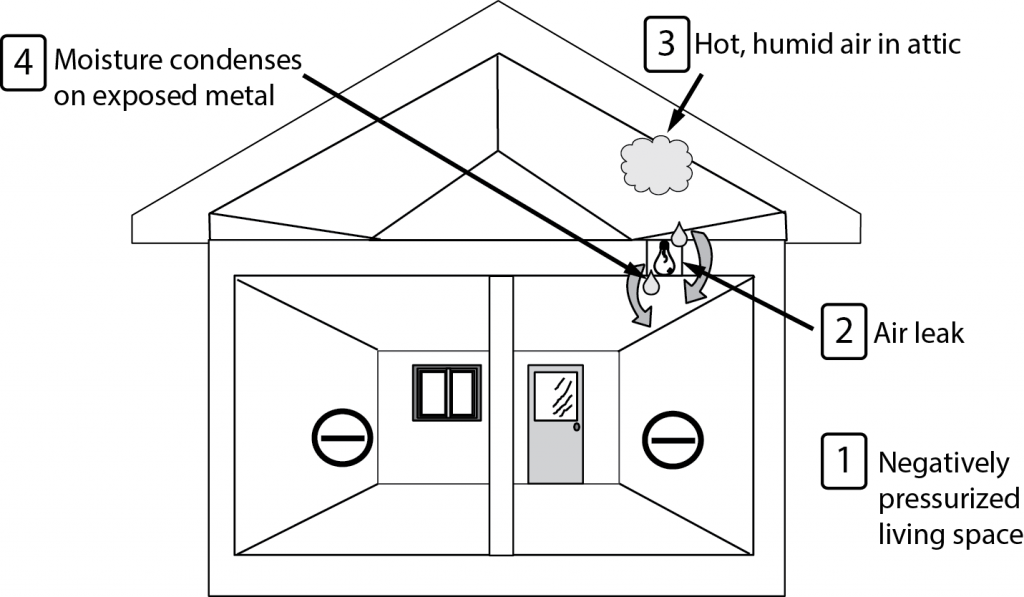

- Sealing recessed lighting fixtures (‘can lights’ or ‘high-hats’), which can leak large amounts of air into unconditioned attic space when the building is under negative pressure (Figure 1).

Homeowners with the time and interest in taking a do-it-yourself (DIY) approach to caulking and weatherstripping can learn more from these resources:

- Caulking & Weatherstripping

- US/DOE Energy Saver – Home Weatherization

- US/DOE Energy Saver – Air Sealing Your Home

- US/DOE Energy Saver – Detecting Air Leaks

- US/DOE Energy Saver – Tips: Sealing Air Leaks

- US/DOE Energy Saver – Weatherstripping

- US/DOE Energy Saver – Caulking

- US/DOE Energy Saver – Improving the Energy Efficiency of Existing Windows

- US/DOE Energy Saver – Savings Project: How to Weatherstrip Double-Hung (or Sash) Windows

- US/DOE – Building America Best Practices Series – Retrofit Techniques & Technologies: Air Sealing A Guide for Contractors to Share with Homeowners

- US/EPA ENERGY STAR® – A Do-It-Yourself Guide to Sealing and Insulating with ENERGY STAR

Homeowners or renters with limited financial means to implement weatherization activities may benefit from the services of a local Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) office if one is available in your area. There are even options available to help manage high home cooling and heating costs though the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP).

Intermediate Weatherization Practices

Intermediate and moderate-cost weatherization practices that can be undertaken by a diligent and experienced DIYer or an appropriate professional might include:

- The application of energy-efficient (e.g., reflective or tinted) window films or solar screens. This practice may be a more cost-effective energy-efficient home improvement solution versus whole-house window replacement in situations where your existing inefficient windows are in good condition and offer satisfactory safety, security, and ease of functionality.

- Installing or upgrading the insulation in ceilings, floors and walls, around ducts and pipes, around water heaters, and near the foundation and sill.

- Sealing air ducts, using the appropriate fiber-reinforced mastic (not duck/duct tape)

- Installing/replacing dampers in exhaust ducts, to prevent outside air from entering the house when the exhaust fan or clothes dryer is not in use.

- Installing gutters, downspout extensions, downward-sloping grading, footing drains, foundation waterproofing membranes, sump pumps, and other techniques to protect the building from both rain and on-site stormwater infiltration.

- Providing proper ventilation to unconditioned spaces to protect a building from the effects of condensation. See Ventilation issues in houses.

- Installing roofing, building wrap, siding, flashing, skylights, or solar tubes and making sure they are in good condition on an existing building.

- Installing storm doors and storm windows.

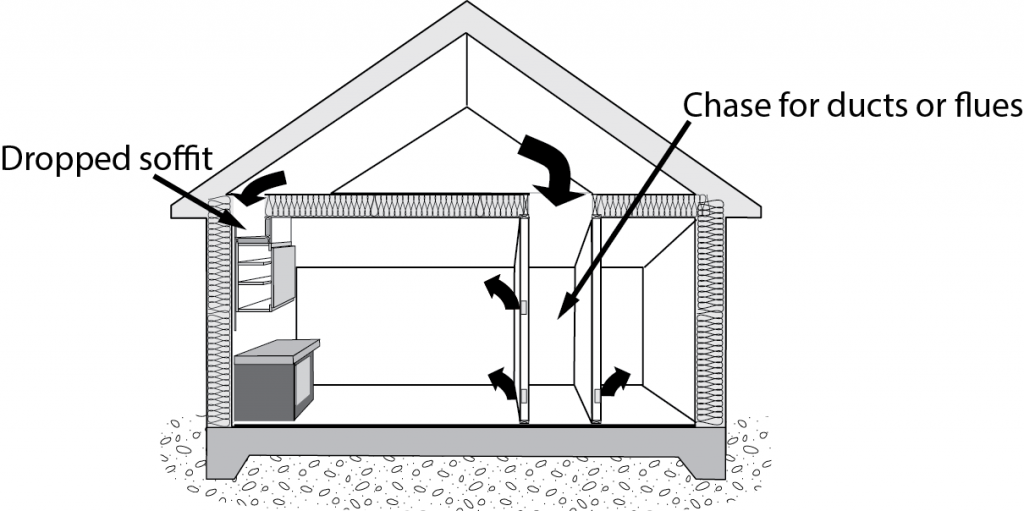

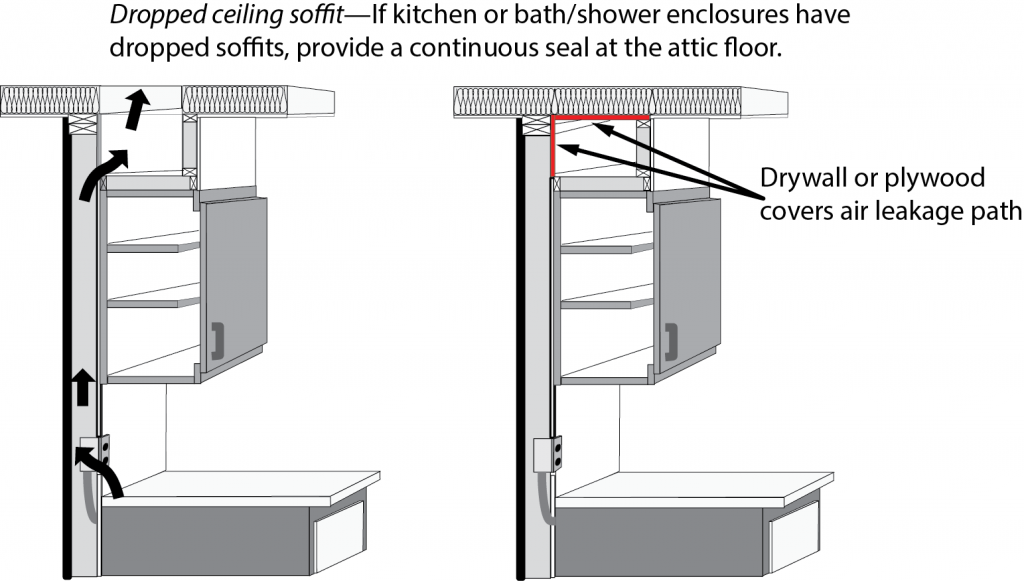

Other measures that might be considered more involved weatherization include key sources of leakage—called bypasses (Figure 2).

Bypasses are hidden from view behind soffits for cabinets, bath fixtures, dropped ceilings, chases for flues and ductwork, recessed lighting fixtures, or insulation (Figure 3). Attic access openings and whole house fans are also common bypasses. Sealing these bypasses is critical to reducing air leakage in a building and maintaining the performance of insulation materials. Table 1 provides examples of commonly-used sealants for various types of leaks.

Table 1. Leaks and Sealants

| Type of leak | Commonly used sealants |

|---|---|

| Thin gaps between framing and wiring, pipes, or ducts through floors or walls. | 40-year caulking; one-part polyurethane is recommended |

| Leaks into attics, cathedral ceilings, or wall cavities above the first floor | Firestop caulking; foam sealant (latex or polyurethane) |

| Gaps, or cracks or holes over 1/8 inch in width not requiring firestop sealant | Gasket; foam sealant; or stuff with fiberglass or backer rod and caulk on top |

| Open areas around flues, chases, plenums, plumbing traps, etc. | Attach and caulk a piece of plywood or foam sheathing material that covers the entire opening Seal penetrations If a flue requires a non-combustible clearance, use a non-combustible metal collar, sealed in place, to span the gap |

| Final air barrier material system | Install airtight drywall approach or other air barrier |

Advanced Weatherization Practices

The more advanced and highest cost weatherization practices involve the complete replacement of existing doors, windows and skylights, and roof. When undertaking weatherization practices of this scale, it’s important to know how to find the right licensed professional contractor and how to select the most appropriate energy-efficient products to meet the unique needs, goals, and objectives of your house and lifestyle. Fortunately, there are extensive ENERGY STAR-certified options to meet your replacement needs for these critical building envelope components.

If you identify the need and choose to replace existing windows, only install National Fenestration Rating Council (NFRC) certified windows and evaluate all windows with eastern and western exposures, as well as any southern-exposed windows without proper shading from awnings or trees. Some other helpful resources related to window improvements and other advanced weatherization practices are listed below:

- BOMA – Comparative Analysis of Retrofit Window Film to Replacement with High Performance Windows

- Energy Saver – Energy-efficient Window Treatments

- Energy Saver – Improving the Energy Efficiency of Existing Windows

- ENERGY STAR – Buildings & Plants: Chapter 7 / Reducing Supplemental Loads – see pp. 10-11, Windows / Window Films

- National Fenestration Rating Council – NFRC’s Window Film Certification and Labeling Program Fact Sheet

ENERGY STAR Windows, Doors, and Skylights

- Efficient Windows Collaborative – Your Gateway to Information on How to Choose Energy-efficient Residential Windows

- US/EPA ENERGY STAR – Residential Windows, Doors, and Skylights

- US/EPA ENERGY STAR – Windows, Doors, and Skylights: What Makes it ENERGY STAR?

- National Fenestration Rating Council – NFRC Fact Sheets for Consumers

- Energy-efficient Homes Series: Windows and Skylights

- US/FTC – Consumer Information: Shopping for New Windows?

ENERGY STAR Cool Roofing

- Radiant Barriers

- The Roof

- US/DOE Energy Saver – Cool Roofs: An Introduction

- US/DOE Energy Saver – Guide to Cool Roofs

- US/EPA ENERGY STAR – Roof Products

- US/EPA ENERGY STAR – Roof Products Key Product Criteria

- Roof Savings Calculator (RSC) Beta Release v0.92

Regardless of the types of weatherization measures undertaken, proper building and equipment maintenance is key. Routine heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system maintenance (e.g., changing the air filter and periodic inspections by an HVAC professional) ensures that the equipment performs as intended, providing both comfort and the designed level of efficiency. The replacement of an HVAC system may also be considered, and proper sizing and installation procedures should be followed.

Indoor Environmental Quality

Weatherization generally does not cause indoor air problems by adding new pollutants to the air. (There are a few exceptions, such as caulking, that can sometimes emit pollutants.) Weatherization measures such as weatherstripping, caulking and sealing, installing more efficient windows, and increasing wall and ceiling insulation should reduce the amount of outdoor air infiltrating into a home. In well thought-out and implemented weatherization strategies to reduce infiltration, the building envelope may need to be tested to ensure proper Air Changes Per Hour (ACH) and provide for mechanical ventilation (see Indoor Air Quality and Energy for more information). EPA also suggests residents should be alert to the emergence of signs of inadequate ventilation, such as stuffy air, moisture condensation on cold surfaces, or mold and mildew growth as a result of making the building envelope more efficient (less infiltration). While weatherization is underway, however, steps should also be taken to minimize pollution from sources inside the home (see Improving the Air Quality in Your Home for recommended actions).

If weatherization activities will involve disturbing existing paint and the home was built prior to 1978, follow EPA recommendation for the project set-up, dust control and proper clean-up of lead-based paint. If using a third party contractor, ensure the firm is certified by EPA (or an EPA authorized state), use certified renovators who are trained by EPA-approved training providers and follow lead-safe work practices.

Disclaimer: Some of the Information provided here comes from EPA’s “The Inside Story: A Guide to Indoor Air Quality“. This information is based on current scientific and technical understanding of the issues presented and is reflective of the jurisdictional boundaries established by the statutes governing the co-authoring agencies. Following the advice given will not necessarily provide complete protection in all situations or against all health hazards that may be caused by indoor air pollution.

Financing Assistance

With the “whole house” weatherization approach, costs include more than just a couple of tubes of caulk and some weatherstripping. Intermediate and advanced weatherization practices require higher up-front costs, but certainly can have an attractive return on those investments. According to the Department of Energy, the value of advanced weatherization practices, on average, is 2.2 times greater than the cost[2]. Basic and intermediate weatherization practices may provide savings for the lifetime of a house—30 years or more.

Consider Energy-efficient Homes Incentive Programs that may be available in your area. There may be other incentives, rebates, or services available in your area offered by utility companies or participating financial institutions. The Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency® or DSIRE, will allow the user to search by county for current financial assistance opportunities available for weatherization and energy-efficient improvements. These may include no-cost performance testing on the building envelope or the duct system.

Added Value of the Florida Energy Systems Consortium

Methods to make homes more energy-efficient, yet still provide adequate ventilation, may originate or be refined from research currently being conducted by faculty affiliated with the Florida Energy Systems Consortium (FESC). From technical research to policy evaluation to behavioral campaigns and community outreach, FESC is helping Floridians reduce energy consumption and demand while creating a healthier environment.

References and Resources

Department of Energy: Energy Saver article on caulking

Florida Weatherization Assistance Program

Florida Weatherization Assistance Program – Local Contact

The Florida Energy Efficiency Loan (FEEL) Program

Acknowledgements

Authors: Craig Millera, Kathleen C. Rupperta, and Hal S. Knowles, IIIa

Reviewers: Bill Lazarb, Donna Carmenc, Susan Schoenherrd, Jennison Kipp Searcya, and Barbara Haldemana.

a Program for Resource Efficient Communities, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

b St. Johns County Housing Partnership, St. Augustine, FL.

c Indiantown Non-Profit Housing Community Action Agency

d Manatee County Community Action Agency

First published April 2015.

This is a fact sheet produced for the Florida Energy Systems Consortium (FESC). The goal of the consortium is to become a world leader in energy research, education, technology, and energy systems analysis.