Introduction

As signed by the Governor on May 27, 2010, Florida House Bill (HB) 7179 created Florida Statute 163.08, which provides counties, municipalities, and special districts [1] with the ability to enter into financing agreements with private property owners to fund qualifying building energy conservation/efficiency retrofits, renewable energy generation, and/or wind resistance improvements with repayment occurring through non-ad valorem property assessments on participating properties. Beginning with California, over 30 states, plus the District of Columbia, have now adopted legislation enabling property assessed financing (PAF) programs for energy related initiatives.

This type of financing mechanism and related variations go by many names including the following:

- Property Assessed Financing (PAF)

- Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE)

- Energy Loan Tax Assessment Programs (ELTAPs)

- Financing Initiative for Renewable and Solar Technologies (FIRST)

- Voluntary Environmental Improvement Bonds (VEIBs)

What is Property Assessed Financing (PAF/PACE)?

Much of the country now refers to the broader sector of “property assessed financing” (PAF) as “property assessed clean energy” (PACE). However, this term may be a misnomer with its focus on “clean energy,” as qualifying property improvements often include energy efficiency, water efficiency, and in Florida’s case, also wind resistance measures. Throughout this fact sheet, we’ve chosen to use the acronym PAF/PACE to minimize confusion in light of this naming trend.

PAF/PACE programs are primarily designed to overcome the “first cost” barrier to households or businesses that would like to pursue qualifying improvements but have limited financial means or motivation to do so (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PACE Financing in 90 Seconds. Credit: PACENow.

Generally PAF/PACE programs involve a local government delineating a “district” (i.e., a geographic boundary for the program), raising capital, and loaning funds to willing property owners within the district. The investment capital used to finance these measures may arise from public and/or private sources, depending on program design. In Florida, these funds can only be used to finance “qualifying improvements” permanently affixed to real property (e.g., homes, commercial buildings) including, but not limited to, the options shown in Table 1.

Program participation is voluntary and assessments are only assigned to property owners who willingly choose to participate and procure an improvement loan. Thus there should be no direct financial impact on non-participating property owners. [2] Assessments are typically paid over a long term (e.g., 10-20 years) as an item on the property owner’s non-ad valorem tax bill.

Table 1. Qualifying Improvements Applicable to Florida PAF/PACE Programs

| Energy Conservation/Efficiency Improvement Options(Section 163.08(2)(b)1.) |

Air sealing and insulating |

| Installing energy-efficient heating, cooling, or ventilation systems | |

| Building modifications to increase the use of daylight | |

| Replacement windows | |

| Installing energy controls or energy recovery systems | |

| Installing electric vehicle charging equipment | |

| Installing efficient lighting equipment | |

| Other similar measures to reduce consumption through conservation or more efficient use of electricity, natural gas, propane, or other forms of energy | |

| Renewable Energy Improvement Options(Section 163.08(2)(b)2.) |

Hydrogen |

| Solar | |

| Geothermal | |

| Bioenergy | |

| Wind | |

| Wind Resistance Improvement Options(Section 163.08(2)(b)3.) |

Improving the strength of the roof deck attachment |

| Creating a secondary water barrier to prevent water intrusion | |

| Installing wind-resistant shingles | |

| Installing gable-end bracing | |

| Reinforcing roof-to-wall connections | |

| Installing storm shutters | |

| Installing opening protections | |

| Other similar improvements |

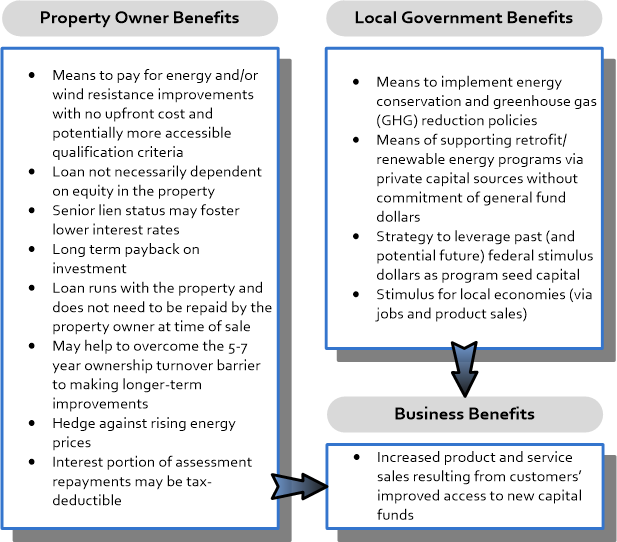

What are the Benefits of PAF/PACE Programs?

Novel approaches (e.g., technologies, policies, financial products) may be necessary to address the complex, interrelated challenges of mitigating climate change, stimulating the economy, and moving beyond carbon/hydrocarbon energy sources. With limited natural, human, and financial capital to invest in potential solutions, PAF/PACE programs may provide local governments one novel approach to helping consumers and businesses to overcome the first cost barrier to clean energy related property improvements (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Local community benefits of PAF/PACE programs. Credit: UF/PREC.

Though energy efficiency, renewable energy, and wind resistance products may be manufactured in places distant from the PAF/PACE program area, the businesses selling the products and the labor necessary to install and maintain them are often a more local affair. PAF/PACE programs may necessitate the spread of new professional knowledge and additional “feet on the ground” in each jurisdiction in which they are implemented. The construction industry in Florida may have the most to gain from these added jobs and new training.

One report estimates, “12.5 direct and indirect full-time equivalent jobs [are] created per $1 million invested in building efficiency retrofits.”[3] This same study suggests compounding benefits beyond job creation, including the following:

“Other social benefits of energy efficiency include improved air quality due to decreased energy generation (which in turn leads to improved public health outcomes), increased property values as the building stock is improved, and gains in consumer spending in other sectors due to lower energy bills, creating a ripple effect of included economic activity” [4]

Now that PAF/PACE programs have been implemented for multiple years in some U.S. cities and counties, analyses of actual program impacts are underway. A July 2011 NREL Technical Report analyzing the ClimateSmart Loan Program (CSLP) provides “a program overview and economic impact analysis of [$9.0 million in] program spending and energy savings [across 598 project invoices] using an input-output (I-O) model…[as well as] a qualitative assessment of factors that affected the resulting economic impacts, and profiles some program participants and contractors.” [5] According to this study, the CSLP, one of the few PAF/PACE programs fully implemented prior to the July 2010 FHFA prohibition (see discussion in a later section), provided measurable economic benefits within Boulder County, Colorado (Table 2).

Table 2. I-O Modeling Outcomes for the Boulder County, Colorado, ClimateSmart Loan Program (CSLP)

| Outcomes | Boulder County, Colorado | Remainder of Colorado Counties |

|

85 |

41 |

|

$5 million |

$2 million |

|

$14 million |

$6 million |

| Additional Findings | ||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

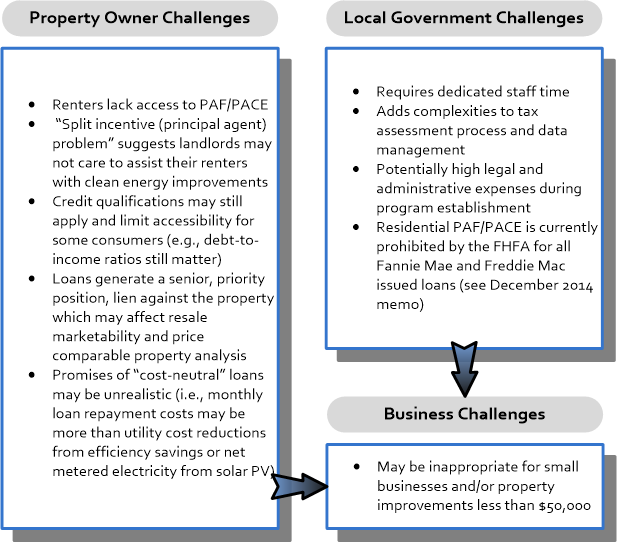

What are the Challenges of PAF/PACE Programs?

While the potential benefits of PAF/PACE programs seem sound on the surface, there are also several clear and present challenges that may limit both the implementation capacity and the programmatic goals of these programs (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Local community challenges of PAF/PACE programs. Credit: UF/PREC.

FHFA Prohibition of Residential PAF/PACE

It should be noted that while PAF/PACE assessment liens are designed by statute to have priority over pre-existing mortgages, lenders have raised concerns regarding this priority issue. Initial prohibition was officially expressed on May 5, 2010 by Fannie Mae in Lender Letter LL-2010-06, “Property Assessed Clean Energy Loans,” stating, “the terms of the Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac Uniform Security Instruments prohibit loans that have senior lien status to a mortgage.” On December 22, 2014, the U.S. Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) issued a “Statement of the Federal Housing Finance Agency on Certain Super-Priority Liens,” strongly reinforcing their long-held position of prohibition of PAF/PACE assessment liens.

“Today, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) is alerting homeowners, financial institutions, and state authorities of the agency’s concerns with state-level actions that threaten the first-lien status of single-family loans owned or guaranteed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. In particular, FHFA is concerned about state actions to create super-priority liens in two instances: 1) through certain energy retrofit financing programs structured as tax assessments and 2) through granting priority rights in foreclosure proceedings for homeowner associations.”

“One such program is known as the Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) program, which often provides loans as first-liens and is offered in California and in some other states. Localities offering these PACE loans threaten to move existing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac mortgages to a second lien position and increase the risk of loss to the Enterprises and, by extension, to taxpayers.”

“In addition to aggressive enforcement of these existing policies, FHFA is continuing to explore other possible remedies and legal actions to protect the Enterprises’ lien position in response to first-lien PACE programs.”

Local governments, property owners, and real estate transaction professionals are strongly advised to stay abreast of these evolving challenges to PAF/PACE as they portend potential local impacts on both the programs and the real estate marketplace. Specifically, the FHFA explicitly prohibits the use of Fannie Mae / Freddie Mac mortgages for the purchase, or refinancing, of any residential properties with an outstanding first-lien PAF/PACE loan. “These restrictions may reduce the marketability of the house or require the homeowner to pay off the PACE loan before selling the house.”

Florida Bills and Legal Appeals

Over the course of the year 2014, several PAF/PACE bond validation appeals were filed with the Florida Supreme Court (Table 3). One of these has already been dismissed prior to oral arguments, two were argued in February 2015, and two were argued in May 2015, though rulings may take many more months. It is not the intent, nor the place, for this fact sheet to consider the merits, nor the context, of these legal actions. These are merely shared as background for the ongoing consideration of PAF/PACE as a financing tool.

However, given the likelihood of continued PAF/PACE opposition from some lobbyists, banks, and federal agencies, it may be prudent for both local governments and PAF/PACE proponents to review these cases and their stated challenges in more detail. Please click through to the case pages via the hotlinks below for the most accurate and up-to-date status of these cases.

Table 3. Florida Supreme Court PACE Bond Validation Appeal Cases

|

Case |

Status |

| SC14-710 “Robert R. Reynolds vs. Leon County Energy Improvement District, Etc. Et Al.” | Active as of June 1, 2015. Oral Argument Held on February 4, 2015. |

| SC14-1282 “Vicki Thomas, Et Al. vs. Clean Energy Coastal Corridor Etc., Et Al.” | Active as of June 1, 2015. Oral Argument Held on February 5, 2015. |

| SC14-1603 “Florida Bankers Association vs. Florida Development Finance Corporation, Etc., Et Al.” | Active as of June 1, 2015. Oral Argument Held on May 7, 2015. |

| SC14-1618 “Robert Reynolds vs. Florida Development Finance Corporation, Etc. Et Al.” | Active as of June 1, 2015. Oral Argument Held on May 7, 2015. |

| SC14-2269 “James E. Gowen vs. State of Florida, Etc., Et Al.” | Dismissed on February 26, 2015. |

Additionally, Florida CS/HB 7067: Economic Development from the 2015 Legislative Session, a bill with implications for PAF/PACE programs in Florida, was filed on March 9, 2015. This bill was opposed by the Florida League of Cities, many counties, and ultimately died in the Commerce and Tourism Committee on May 1, 2015. However, it contributed to the ongoing debate about the role and structure of PAF/PACE programs by proposing an expansion of the financing power of the Florida Development Finance Corporation (FDFC) to “issue bonds without authorization from a public entity and authorizes FDFC to levy a special assessment on participants in local Property Assessed Clean Energy programs.” [6]

HUD Unlocks PAF/PACE Financing for Multifamily Housing in California

While residential PACE has been constrained by the perpetually prohibitive position of the FHFA, commercial PACE faces fewer challenges. In fact, on January 29, 2015, the multifamily residential sector received significant federal support and guidance “to remove existing barriers and accelerate the use of PACE financing” via a partnership between the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the State of California, and the MacArthur Foundation. This pivotal partnership entails several initiatives as excerpted from the press release and quoted below.

“Governor Brown is establishing a California Multifamily PACE Pilot in partnership with the MacArthur Foundation [via at least $10 million in impact investments to create and expand the California PACE and On-Bill Pilots, and explore other innovations, including the use of Pay for Success]. The Pilot will enable PACE financing for certain multifamily properties, including specific properties within HUD, the California Department of Housing and Community Development, and the California Housing Finance Agency’s portfolios, opening up financing to an entire segment of commercial PACE projects.”

“Secretary Castro is issuing guidance clarifying the circumstances under which HUD can approve PACE financing on HUD-assisted and-insured housing in California.”

“The U.S. Department of Energy is committing to work with the State of California to design and undertake a study assessing the performance of California’s PACE program as data becomes available.”

“HUD is committing to support the State of California in creating an innovative California Master-Metered Multifamily [On-Bill Repayment] Finance Pilot Project…the $3 million program of technical assistance and credit support may include a loan loss reserve and/or a debt-service reserve fund.”

Additional PAF/PACE Barriers and Potential Strategies to Redress

When implementing a PAF/PACE program for energy, wind resistance, or other qualifying improvements, a local government must acknowledge and address other potential barriers to individual action beyond first costs including the following: [7]

- Lack of information

- Transaction costs

- Lack of confidence in expected or anticipated savings

- Split incentives [8]

- Length of payback

To overcome these barriers, the proponents of PAF/PACE believe that local governments should start from the premise that a successful energy finance program puts a participating property owner in a breakeven or better financial position in terms of savings relative to assessment payment (i.e., a “savings-to-investment (SIR)” ratio greater than one). This breakeven premise, while ideologically sound, may not be rooted in evidence-based building science. [9] [10] [11] [12] Accurate accounting for any hypothetical breakeven point requires, at a minimum, an analysis of the relationship between the following criteria: [13] [14] [15]

- Property owner’s historical utility consumptive use data/costs and insurance costs [16]

- Combined financial value of the projected energy/water/insurance savings potentially achievable each month

- Loan repayment term as it relates to the useful life of the improvements

- Loan interest rate

- Reserve funds necessary to accommodate requirements of the financing sources for local government administration of the program

- Any application or other property owner advanced fees

- Any interest rate buy down funds from public and/or private collaborators, grants, etc.

- Any rebates or incentives from federal, state, and/or local policies or manufacturers available at the time of property owner improvement installation

Additional PAF/PACE Considerations in Florida HB 7179

In addition to delineating the qualifying improvements allowed to be financed with PAF/PACE mechanisms, Florida HB 7179 lays out guidelines and requirements for PAF/PACE programs including, but not limited to, the following:

- Local Government Administrative Requirements: No delinquent liens or non-current debt will be allowed on participating properties.

- Limits on Assessment Amounts: Non-ad valorem assessments may not exceed 20% of county property appraiser’s just value for participating mortgage-encumbered properties without prior lender consent or energy audits that suggest monthly savings will exceed new assessment costs.

- Program Administration: Either a for-profit entity and/or not-for-profit organization may administer the program on behalf of the local government.

- Funding Sources: Local governments may incur debt payable from participating non-ad valorem property tax revenues or any other available revenue source authorized by law.

- Existing Mortgages: At least 30-day advance notifications of intent to existing loan holders/servicers must be given and include maximum principal to be financed and maximum annual assessment needed for repayment. No prohibition on escrow increases necessary to pay for annual qualifying improvement assessment is permitted.

- Collection as Non-Ad Valorem Assessment: Financing repayment may be collected by non-ad valorem assessments.

- Collaboration Among Local Governments: Local governments may partner in creating/implementing PAF/PACE programs.

- Licensing: Any work requiring a license to make qualifying improvements must be performed by a contractor that is properly certified or registered through the appropriate licensing board.

- Notice to Subsequent Purchasers: A state-mandated disclosure statement must be provided in large, boldface and conspicuous type that is located immediately prior to the space reserved in the contract for purchaser signature.

- Utility Provider Restrictions: Provisions in agreements between local governments and public or private power or energy providers or other utility providers to limit or prohibit any local government from exercising its authority under Florida HB 7179 are not enforceable.

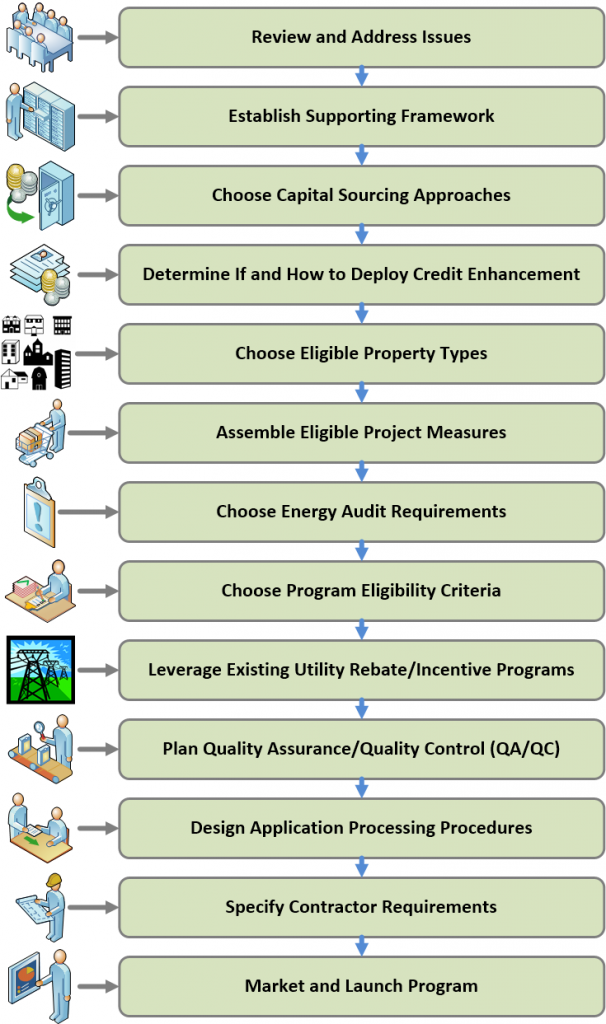

PAF/PACE Program Process

There are numerous steps involved in the process of establishing, developing, and implementing PAF/PACE programs. For more detailed explanations of all 13 steps identified by the U.S. Department of Energy (Figure 4), visit their Clean Energy Finance Guide: Chapter 12. Commercial Property-Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) Financing. These process steps in program formation and administration require four major categories of services: (1) technical (e.g., training, auditing, and inspection); (2) financial (e.g., modeling and underwriting); (3) legal (e.g., counsel and document development); and (4) administrative (e.g., application processing, customer support, and fund disbursement).

Figure 4. An overview of the major steps necessary for launching a PAF/PACE program. Note, actual program creation may take a different order and may include more (or less) steps than this general overview. Credit: UF/PREC, derived from US/DOE (Pages 12-3 to 12-4).

The Florida Context

Florida House Bill 7179 does not prescribe a process for formation of a PAF/PACE program. The legislation requires only that the program be established by resolution or ordinance at the local governmental scale. However, there are certain administrative requirements that do not impact program formation but will be relevant in ongoing administration. Therefore, local governments have broad discretion in how to form and deploy their programs. One possible model is exemplified in the 13-step process laid out in Figure 4.

As of the summer of 2015, the nonprofit PACENow: Financing Energy Efficiency reports that two PAF/PACE programs are active in 33 municipalities across 9 counties within Florida, with another 17 municipalities active within Miami-Dade County from an additional program not reported on the PACENow list. Just as legislation and legal action at federal, state, and local levels contributes to a highly fluid and evolving context for PAF/PACE, the actual programs and implementation are also in flux. These programs and their coordinating entities are subject to change.

U.S. EPA Financing Program Decision Tool

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) provides an online decision support tool to assist state and local governments with consideration and development of renewable energy and energy efficiency building improvement financing programs. Through a series of questions on target markets and available resources, the tool filters for the most applicable potential financing program options.

While PAF/PACE is not a panacea, under optimal circumstances, controlling for known challenges, and given appropriate capital investment sources and financing structures, these programs may make sense for multiple property markets in many jurisdictions.

References and Resources

See the following links for more information about PAF/PACE and other mechanisms to fund energy conservation/efficiency, renewable energy, and GHG emissions reductions:

- D’Arelli, P., Jones, P., & Ostema, L. L. (October 2010). Options for Clean Energy Financing Programs: Scalable Solutions for Florida’s Local Governments. University of Florida Program for Resource Efficient Communities. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Florida House Bill 7179: Qualifying Improvements to Real Property. (Select “Regular Session 2010” in drop down menu and type “7179” in “Bill Number” field). Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Fuller, M. (May 21, 2009). Enabling Investments in Energy Efficiency: A Study of Energy Efficiency Programs that Reduce First-Cost Barriers in the Residential Sector. California Institute for Energy and Environment. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Goldberg, M., Cliburn, J. K., & Coughlin, J. (2011). Economic Impacts from the Boulder County, Colorado, ClimateSmart Loan Program: Using Property-Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) Financing. Report Number: NREL/TP-7A20-52231. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Gonzales, G. (2015). Administration and California Partner to Drive Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in Multifamily Housing (Press Release No. 15-011a). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- Hendricks, B., Goldstein, B., Detchon, R., & Shickman, K. (August 2009). Rebuilding America: A National Policy Framework for Investment in Energy Efficiency Retrofits. Center for American Progress; Energy Future Coalition. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA). Property-Assessed Clean Energy. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- Speer, B., & Koenig, R. (2010). Property-Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) Financing of Renewables and Efficiency (p. 4). Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- Trojan, N. (2012). Lender Support Study: Enhancing the Commercial Real Estate Lender Consent Process for PACE Transactions (p. 16). Pleasantville, NY: PACENow. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- U.S. Department of Energy. (March 2013). Clean Energy Finance Guide: Chapter 12. Commercial Property-Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) Financing. 3rd Edition. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- U.S. Department of Energy. (May 7, 2010). Guidelines for Pilot PACE Financing Programs. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) Solution Center. Financing for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. State and Local Climate and Energy Program: Clean Energy Financing Programs. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

Acknowledgements

Authors: Hal S. Knowles IIIa, Paul D’Arellib, and Pierce Jonesa

Reviewers: Ted Kuryc (2010 and 2015), Barbra Larsond (2010 and 2015), Sean McLendone (2015), Rachel Waynee (2015), and Holly Bannerf (2015)

a Program for Resource Efficient Communities, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

b Florida Zoning Law Group; National Development Advisors, Plantation, FL

c Public Utility Research Center, Warrington College of Business Administration, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

d Soil and Water Science Department, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

e Office of Sustainability, Alachua County, FL

f Growth Management Division, Alachua County, FL

First published June 2010. Revised June 2015.

This is a fact sheet for the Florida Energy Systems Consortium (FESC). The goal of the consortium is to become a world leader in energy research, education, technology, and energy systems analysis.

Footnotes

[1] Both independent and dependent special districts can be organized pursuant to F.S. 163.08.

[2] However, as described in other sections of this fact sheet, there may be indirect financial impacts to taxpayers and other non-participants through the complex relationships of lien prioritization and real estate transactions.

[3] Rebuilding America: A National Policy Framework for Investment in Energy Efficiency Retrofits, Center for American Progress and Energy Future Coalition, August 2009, p. 8. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

[4] Ibid, p. 12.

[5] Goldberg, M., Cliburn, J. K., & Coughlin, J. (2011). Economic Impacts from the Boulder County, Colorado, ClimateSmart Loan Program: Using Property-Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) Financing. Report Number: NREL/TP-7A20-52231. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

[6] Florida Association of Counties. (2015, April 22). Lobbytools.com: House omnibus economic development bill passes last committee with changes. FAC News Clips – Economic Development Category. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

[7] Excerpted from US DOE EERE State and Local Solution Center: Financing. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

[8] “Split incentives occur when the decision-maker does not receive many of the benefits of the improvements. An example is the case of rental property owners who lack incentives to invest in building efficiency upgrades when the tenant pays the utility bill.” US DOE EERE State and Local Solution Center: Financing.

[9] Jones, P., Taylor, N., & Kipp, J. (2012). Housing Stock Characterization Study: An Innovative Approach to Measuring Retrofit Impact (Subcontract Report No. SR-5500-54891; DOE/GO-102012-3594) (p. 54). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

[10] Jones, P., & Vyas, U. (2008). Energy Performance in Residential Green Developments: A Florida Case Study. Real Estate Issues, 33(3), 65–71. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

[11] Jones, P. H., Vyas, U. K., Taylor, N., & Kipp, M. J. (2010). Residential Energy Efficiency: A Model Methodology for Determining Performance Outcomes. Real Estate Issues, 35(2), 41–47. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

[12] Jones, P. H., Taylor, N. W., Kipp, M. J., & Knowles, H. S. (2010). Quantifying household energy performance using annual community baselines. International Journal of Energy Sector Management, 4(4), 593–613. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

[13] “Pilot programs should collect the data necessary to evaluate the efficacy of PACE programs. Examples of typically collected data would include: installed measures, investment amount, default and foreclosure data, expected savings, and actual energy use before and after measures installation. To the extent possible, it’s important that programs have access to participant utility bills, ideally for 18 months before and after the improvements are made. The Department of Energy will provide more detailed information on collecting this data, obtaining permission to access utility bills, and how to report program information to enable a national PACE performance evaluation.” U.S. Department of Energy. (May 7, 2010). Guidelines for Pilot PACE Financing Programs. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

[14] Stein, J. R., & Meier, A. (2000). Accuracy of home energy rating systems. Energy, 25(4), 339–354. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

[15] Mills, E. (2004). Inter-comparison of North American residential energy analysis tools. Energy and Buildings, 36, 865–880. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

[16] Meier, A. (2009, April). Editorial: How Private Should Utility Bills Be? Home Energy, 26.2, 2. Retrieved June 1, 2015.